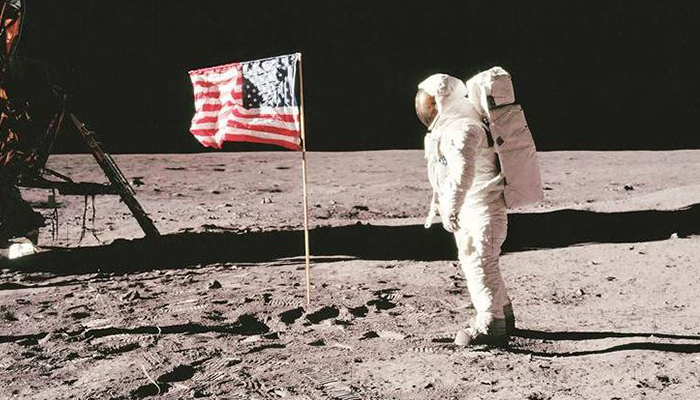

The U.S. was the first country to put a person on the moon when Neil Armstrong bounded from the Apollo 11 staircase onto the lunar surface on July 20, 1969. I was drawn to this case after reading a book in which several NASA employees attested to feeling strongly connected to the organization's goals an aspirations - a perception many said they had never experienced outside of this period at NASA...

James McLane, chief of NASA Space Environment, said, "I can remember when no matter what came along, we used to say to each other, 'We've got to get that man on the Moon,' and mean it. We really meant it, you know..."

Flight director Gene Kranz exclaimed, "We are going to write the history books and we're going to be the team that takes an American to the moon..."

Lola Parker (a secretary) noted, "I don't know of anybody who was a clock puncher. No matter what role they played, that was in the back of their mind: we've got that man to get to the moon..."

Another telling example was that of Charlie Mars. As an electrical engineer, he was far removed from landing on the moon in an objective sense, yet he identified his actions as if he was going to the moon: "One of the things we had was a common goal; and we all realized that we were into something that was one of the few things in history that was going to stand out over the years. 'We're going to the Moon. We're putting a man on the moon!...'"

James Jaaz said that despite working in low-status roles long before the moon landing - including as a "data runner" and an "extra body" who ran errands - he felt a personal connection to NASA's core objective, and he spoke as if everyday actions represented the ongoing achievement of landing on the moon: "Being a 'data runner' was a great experience... I shared... the overwhelming sense of accomplishment felt by my co-workers. I believed that landing on the Moon was what NASA did and was proud to be a part of it..."

When astronaut Scott Carpenter was asked in an interview to discuss orbital flight and control systems, he responded in a way suggesting that he did not construe his work in terms of these everyday actions. Instead, echoing his belief that the moon was a "high purpose"..., he described his work in terms of the aspiration that the moon stood for: "We... continue to expand our knowledge of the universe, hopefully for the benefit of all mankind..."

Notably, the construal of day-to-day work as "going to the moon" was not limited to astronauts and engineers but extended to employees at all levels - including secretaries and interns. This reality echoes a legend in which Kennedy, touring NASA headquarters, encountered a custodian mopping the floors. Kennedy asked the employee, "Why are you working so late?" The custodian responded, "Because I'm not mopping the floors, I'm putting a man on the moon."

"I'm Not Mopping the Floors, I'm Putting a Man on the Moon": How NASA Leaders Enhanced the Meaningfulness of Work by Changing the Meaning of Work. by Andrew M. Carton. Administrative Science Quarterly. 2018. Vol. 63(2)323-369